cave

cave The Cave - Home Of The Cellar Rat

Wednesday, February 23, 2011 at 1:23PM

Wednesday, February 23, 2011 at 1:23PM  Home Sweet HomeThe Cave is really home to the Cellar Rat, which is why I'm surprised that I haven't spoken more about it. The obvious question is why put wine in a cave in the first place? Wine is picky about its environment. It ages best in a very specific temperature and humidity range that remains constant. Serendipitously, shallow caves happen to provide exactly such an environment. Another modern solution to wine aging and storage is the climate controlled warehouse. It takes a great deal of energy to cool such a large space, so caves are really a much greener option and cost effective as well - I have it on good authority that building a cave is less expensive per square foot than any other structure. Building a modern wine cave is a very exciting endeavor. The digging machine that buried into the earth like a massive mechanical mole looked like the imaginings of Jules Verne.

Home Sweet HomeThe Cave is really home to the Cellar Rat, which is why I'm surprised that I haven't spoken more about it. The obvious question is why put wine in a cave in the first place? Wine is picky about its environment. It ages best in a very specific temperature and humidity range that remains constant. Serendipitously, shallow caves happen to provide exactly such an environment. Another modern solution to wine aging and storage is the climate controlled warehouse. It takes a great deal of energy to cool such a large space, so caves are really a much greener option and cost effective as well - I have it on good authority that building a cave is less expensive per square foot than any other structure. Building a modern wine cave is a very exciting endeavor. The digging machine that buried into the earth like a massive mechanical mole looked like the imaginings of Jules Verne.  Cave FloorplanThe process of digging the cave, we discovered, is very organic: You start with a plan of what you want and then the foreman comes back to you halfway through and says "Okay, we hit granite. You can keep going the way it says on the plan and it will cost you $100,000 or you can go this way and it will cost $10,000." On the original plan the cave is designed like a wheel with spokes leading into the center. It was definitely destiny morphed into the current configuration because the finished cave layout is in the shape of a wineglass.

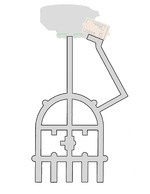

Cave FloorplanThe process of digging the cave, we discovered, is very organic: You start with a plan of what you want and then the foreman comes back to you halfway through and says "Okay, we hit granite. You can keep going the way it says on the plan and it will cost you $100,000 or you can go this way and it will cost $10,000." On the original plan the cave is designed like a wheel with spokes leading into the center. It was definitely destiny morphed into the current configuration because the finished cave layout is in the shape of a wineglass.

They use the massive machine to dig and cart away the dirt and then they cover the walls with spray-on concrete called shockcrete. The shape of the tunnels provides the real strength of the cave, however, where the winery building will eventually sit on top of the cave, steel girders are stretched into an arch which can hold an enormous load. The strength of this shape has been known since Roman times. Interestingly, it is the concrete floor that holds the ends of the girder in place, so the floor is really what keeps everything together as you can see in the diagram. Another layer of shockcrete is applied and then they cover it with whatever finish you like, such as plaster. In all of the working sections of the cave we left the shockcrete bare because it looks nice but it turned out to be the bane of cellar rats - its jagged surface is as treacherous as volcanic rock. It's slow going when you're working in the tight space between the wall and the barrels.

Deerfield's cave is state-of-the-art: Compressed air is provided throughout the cave, as well as lines for inert gases like nitrogen and argon. There is even copper wire buried in the floor to provide wireless signals! My uncle Martin, our General Manager, even hooked up every switch to our main server, so that potentially, if you wanted to, you could dim the lights from Paris.  The Tasting RoomThe cave is 23,000 sq. ft. and holds about 3000 barrels - that's a lot of wine! Unique to Deerfield's cave is the Grand Room which lays in the very heart of it. This amazing space is currently where our tasting room is located, so when you visit you get to go spelunking. Deerfield’s caves were designed by the winemaker’s brother and my father, Michael Rex.

The Tasting RoomThe cave is 23,000 sq. ft. and holds about 3000 barrels - that's a lot of wine! Unique to Deerfield's cave is the Grand Room which lays in the very heart of it. This amazing space is currently where our tasting room is located, so when you visit you get to go spelunking. Deerfield’s caves were designed by the winemaker’s brother and my father, Michael Rex.

cave

cave The Pink Juice

Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:51AM

Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:51AM  Sometimes it seems like the world of wine has had a line drawn in the sand. On one side there are fruity and light white wines and on the other side there are the structured and more tannic reds. But occupying the no-mans-land between these two different worlds is Rosé. Neither a true white or a true red, this pink juice shares characteristics of both.

Sometimes it seems like the world of wine has had a line drawn in the sand. On one side there are fruity and light white wines and on the other side there are the structured and more tannic reds. But occupying the no-mans-land between these two different worlds is Rosé. Neither a true white or a true red, this pink juice shares characteristics of both.

All red wines draw their color from the skins of the grape and in this sense Rosés are no different. There are several different techniques that winemakers use to achieve the distinctive style of Rosé. Sutter Home's technique which it uses to produce their um...ubiquitous...*ahem* White Zinfandel is the product of a winery accident where red wine was accidentally added to a white wine tank and to this day, most of the Rosés on the market are produced by simply blending red and white wines. Alternatively, when the winemaker’s intent is to produce a Rosé from the beginning, grapes are harvested at very low Brix to achieve a light wine with low alcohol. Unlike red wines that are fermented along with their skins throughout the entire process of primary fermentation, Rosés are only briefly in contact with their skins before they are pressed, often only for as short a period as a few hours.

Deerfield uses a traditional approach to making Rosé. Deerfield produced a Rosé in 2009 and our latest one, the 2010 Checkerbloom Rosé, was just released this past week. Deerfield uses a traditional process known as Saignée (which means "bleeding off") to make our Rosé. In this process grapes that are picked at a high Brix, which have too much sugar that will likely produce a wine with too high alcohol yet beautiful ripe fruit flavors, are macerated and some of the juice is "bled off" to reduce the skin to must ratio. This extra juice is ideal for creating a Rosé. Rosé can be made out of many different varietals or a blend. The juice we use to produce our Rosé was bled off of our 95 point Old Vine Zinfandel which invariably is harvested at high Brix. Already colored by its contact with the skins, we treat the juice quite differently than either a normal red or white fermentation. We ferment at a low temperature to slow the process, and in neutral oak barrels which is typically a treatment we reserve for Chardonnay. The barrel fermentation develops softer tannins and lengthens the mouthfeel. Even though this wine is fermented without its skins like a white wine, we use a strain of red wine yeast that is known to accentuate the fruit character. This is what makes our Rosé stand out - it has bold fruit flavors and body, yet it is light and approachable.

rose,

rose,  winemaking

winemaking Tannin - The Shape Of Wine

Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM

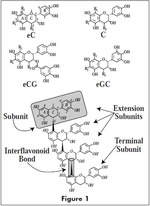

Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM  Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

It’s a tricky concept to translate to words. We’re visual creatures and humans have developed a huge vocabulary to communicate to one another things we see. But there wasn’t a word for red, how would you describe it to someone else? …or to someone who’s never seen it? That’s the challenge of describing the sensation of taste: There simply isn’t a vocabulary that belongs to it. Wine drinking is a social experience, however, and enthusiasts yearn to share it with others so have borrowed from the visual realm to describe the incorporeal attributes of taste. Often shapes are used to describe the sensation of tannin: rounded, edgy, linear or pointy are things you might hear.

Tannins can be found all over. In fact, tannins are an integral part of all fruit flavor. The seed of every fruit has tannin. You might notice it when you suck on a cherry or peach pit. Grapes however have unique tannins that offer a distinct experience from tannins found in other fruits. Almost all cream of tartar found on the market today is made using tannins extracted from grapes. Though you don’t analyze the sensation of biting into an apple as critically as you might sipping wine, you would certainly notice and miss the tannin if it was gone.

Fruit isn’t the only place that we find tannin however. A vital reason that oak shares such an affinity with grape juice is that its own native tannins serve to compliment or contrast with the tannin found in grapes. All wood has tannin in it. Cherry and redwood both have very soft tannins and though they are nowhere near as heavily used in winemaking as oak is, they lend their tannins to wine with favorable results. Even within the oak family, the different species of oak tree (French, American and Slavonian) have distinctive tannin structures of their own. Oak tannins tend to be more “edgy” or “rectilinear”, and it’s this contrast to the more rounded tannins found in grape skins that can create complexity. The cooperage (barrel maker) can redefine the nature of the oak tannin by the manufacturing process. By toasting the barrel at cooler temperatures and by air drying it for longer periods of time, the cooper can round the corners of the tannins producing an oak that is more complimentary instead.

Clearly there’s a great deal of diversity of tannins out there. Every cluster of grapes contains several different types of tannin. The tannin in the stems, skins and seeds are all very different and while it’s generally agreed upon that the tannins found in the stem are too harsh and not ideal to include in the fermentation, there is debate about the quality and character of tannins found in the seed and skin. The prevailing opinion has been that seed tannins are harsher than skin tannins and therefore ought to be removed. Robert Rex disagrees with this notion and instead believes the reverse is true, which is a view shared by Dr. Roger Boulton, professor at UC Davis. Robert’s reasoning is that we use a fairly uncommon process known as whole berry fermentation where the grapes are never crushed and instead the juice ferments inside the berry. The difference is that the skins are never ripped apart, releasing the harsh tannins found inside. Our wines have notably soft tannins even though they are fermented along with all their seeds. Robert concluded that the least common denominator must therefore be the skins. Seed tannins tend to add structure to the center of the palate while skin tannins slide toward the back.

Tannin can be described as a sort of drying effect and if you ever have had a sip of wine and felt as if it coated the roof of your mouth, it was because there was too much tannin. To remove tannin, winemakers often make use of fining agents. In California, gelatin is commonly used and in France egg whites are the norm. At Deerfield, because of our gentle production techniques, we very rarely need to make use of fining agents and for that reason we are able to make wine that is vegan friendly.

Even white wines have a small amount of tannin in them. Almost all of the tannins are found in the skin and seeds which are immediately removed by pressing before white wine is fermented. Although our high-tech presses the grapes extraordinarily gently, some of the tannin from the skin is squeezed out. Furthermore, alcohol is the most effective agent at extracting tannins from the other parts of the grape and because the skins and seeds are removed before the alcohol is present (since the juice has not yet fermented), there are fewer tannins found in white wine.

The truth is that even the experts are dealing with an imperfect picture of exactly how tannin interacts with our taste buds. In this article Dr. James Kennedy presents a number of different theories as to the exact cause of the perception of tannin in wine. What we do know is that tannins gain complexity over time. As the years go by, all sorts of different flavor and color compounds floating in suspension in the wine combine with the tannin giving rise to endless new iterations. That’s why wine changes so dramatically with the passage of time and can sometimes go through periods of awkwardness or exceptionality.

tannin,

tannin,  winemaking

winemaking Fleeting Fancy

Friday, April 1, 2011 at 4:02PM

Friday, April 1, 2011 at 4:02PM I thought I’d take a break from my more informative encyclopedic posts and do something a little more editorial. The wine industry encompasses such a huge body of knowledge, from chemistry to soil science, wood working to viral marketing that sometimes I get so involved in the process of producing wine that I lose sight of why humans put so much effort into crafting the highest quality wines the world has ever seen. What’s so special about wine that it has developed into a worldwide phenomenon? Why is it that in the pantheon of Greek gods, Dionysus, the god of wine, sits among the elite Olympians? I don’t remember Frank, the god of mead, sitting on a throne next to Zeus. Moreover, wine has created a subculture that is woven into the fabric of many different societies. Wine lovers from across the globe seek each other out in a variety of forums to share their experience and passion. So what’s with all the hubbub?

Wine represents a truly unique substance, not just unique in the sense that it is different from all other food and beverages, but also in the sense that every vintage is unique, further diversified by the conditions of the region, the varietal, the vines, the winery that produced it, the technique, the artistry of the cooper, etcetera etcetera. The complexity of the chemical composition of the grape itself and the stupefying amount of variables involved in producing a particular wine, make duplicating it an impossible task. This stands in stark contrast to beer, which can be exactly reproduced following a recipe, to the extent that generally no difference is discernable. Any wine enthusiast will tell you that a good bottle of wine is a reflection of the time and place from which it came.

There’s a fourth dimension to wine as well: Time. Wine isn’t like a snapshot of the year that it was produced. Sometimes the cork gives us the impression that the wine is hermetically sealed and existing apart from the rest of the world, but this couldn’t be farther from the truth. It’s not a frozen in time but instead is a living thing that changes as it ages, just like the rest of us. It might take time to find itself when it’s young; have a particularly awkward adolescence; then blossom into maturity and age gracefully. Or it might go the way of Jim Morrison, and live fast and die young. Wine is ever changing. Incorporated into this idea, is that drinking wine is an experience that we have, and like a moment in time, no experience can ever be replicated. So you might have enjoyed a wine at a fun dinner party with close friends and its impact is different than it might be if you enjoyed that same wine winding down from a long day.

So my theory is that wine occupies such a unique place in our culture precisely because it is a fleeting experience. The sensation of wine on our palate is so ephemeral. Perhaps that’s why we prize wines that linger on tongue, better known as wines with a long finish. Subconsciously, when we uncork a bottle, we are searching for a familiar experience we had enjoyed before or are in search of a new and exciting one. Maybe it’s this reflection of life that draws us in and enchants us. Oh, and sometimes it tastes good too.

love of wine

love of wine Back-to-Back Harvests - Northern California to Southern Australia

Friday, April 15, 2011 at 10:44AM

Friday, April 15, 2011 at 10:44AM This post was written by comrade Cellar Rat, Ryan Rugg C.S.W. (Certified Specialist of Wine), who has departed Deerfield's cave to chase the harvest across the globe! While the vines are just beginning to bud in the Northern Hemisphere the grapes have fully ripened in the Southern Hemispheres. For the love of winemaking, Ryan's followed the grapes to the other side of the Earth and here he contrasts his experience in Australia with making wine at Deerfield.

As a former colleague and current Cellar Rat/Harvest Chaser myself, I ventured from the depths of the Deerfield caves to the sunny outback of South Australia for a vintage “down unda” to see things done a different way and to learn a new perspective on winemaking. The point of this story is to explain the differences between winemaking and viticulture styles in two very important, distinct, and completely different places on earth. To begin, I must lead you into the past for a moment. The year is 2010; the location, Sonoma Valley, California. We never really had much of a summer due to cloudy overcast skies during our “normal” 180-200 day growing cycle with daytime temperature not reaching more than 80 most of this time. To the layman, this makes for a fantastic Northern California summer; for the grape grower, a near disaster. If there is no sunlight, we don’t achieve photosynthesis and the fruit doesn’t fully ripen. To compensate for the cool summer, we made efforts to thin the canopy of the vines to open the grape bunches up to the sun for a bathe if you will. Then, our worst nightmare occurred, three straight days of sweltering heat ranging from 103-111 degrees Fahrenheit. Grapes on the valley floor and grapes facing west incurred the wrath of the sun and heat. They shriveled to nearly nothing, looking more like raisins than grapes. As if this wasn’t enough damage, we had some mid-harvest rains that brought botrytis cinerea and multiple forms of mildew to the grape bunches. In turn, leaving most producers with a limited and reduced crop in 2010. It is a pity, though Mother Nature has her ways and the wine industry must abide, cope, and carry on. On the up-side, myself and several other harvest workers for Deerfield Ranch Winery saw light at the end of the tunnel when techniques instituted buy Head Winemaker (and Master) Robert Rex seemed to turn the idea of a “bad vintage” into a winemaker’s vintage. This is what makes a great winemaker and winery stand out each and every vintage. When great fruit comes in, it is said to almost make itself; when the year is a challenge, it is said to “separate the men, from the boys”. There is no doubt in my mind that we made fantastic wines out of the grapes we processed due to the measures taken by Robert Rex and associate winemaker, Cecilia Valdivia, in 2010.

Now, let us switch gears to a place far removed from California. It’s 2011 and harvest (vintage as the Aussies call it) is nearly on its way. The summer has been moderate to warm at best with little full sunlight and temps only reaching 100 degrees a mere week total for the entire growing period. But unlike California, the vines are “trained” much differently. The canopy is full, heady, and leaves are a-plenty. This is due to the extreme UV ray put off by the sun on this side of the world and the opening in the ozone layer. Much to my surprise, they do not tend vineyards with “people” but with heavy machinery, so canopy thinning is only done on the smallest of vineyards. As seen in the news, Australia from its middle to east has had record floods, bringing them out of a 9 year drought. For vines that have been use to the stress of no water, and have buried their roots deep, they have no idea what to think as the rain soaks the earth and washes away the surface. This left humid cool-warm temps that inevitably turned to powdery mildew, downy mildew, and latent botrytis (the bad kind). Most vintners in the Barossa have never experienced such strife and most say it has not happened like this since 1974!

As a wine professional (not an expert) myself, I have come to terms with what mother nature can do though I realize that bad years and bad weather come and go but wine will never leave. We are steady making this year’s wine despite the odds. Yes, quality takes a back seat to a year of this caliber but never write off a vintage entirely due to critique and commentary. Let YOUR palate be the judge.

Notable differences in winery work in California and South Australia:

South Australia

Little to no use of hand picking, hand pruning (all done by machine)

Safety regulations are much stricter in the vineyard and in the winery.

Little to no organic practices applied to viticulture (only one certified in the Barossa Valley)

No water can be added to wines for sugar dilution (ie. High alc wines are the norm)

Irrigation is king and more of an art than science in this region of the world

Soils are the most decomposed in the world, with ironstone and red sand predominately; alkaline rich and high in acid low in nutrient.

The region has been making wine and growing grapes since 1788, tradition is the base, so very little “experimentation” in winemaking practices.

Northern California

Hand picking, vineyard management, and hand pruning are essential

Sustainable, Organic , and Biodynamic practices in the vineyard are key to a healthy vine and resulting wine.

Water can be added, though not preferred, if so a nice rose can be the result of the saignée.

Irrigation is key though not always needed due to a wet winter and spring before budbreak and fruit set.

Soils are very diverse, as is the climate in many “micro” areas (Sonoma County has 118+ different soils)

Although winemaking and viticulture have been an integral part of California history, it has not been around for as long though experimentation to achieve the best quality is key to its place in the world of wine.