tannin,

tannin,  winemaking

winemaking  Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM

Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM  Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

It’s a tricky concept to translate to words. We’re visual creatures and humans have developed a huge vocabulary to communicate to one another things we see. But there wasn’t a word for red, how would you describe it to someone else? …or to someone who’s never seen it? That’s the challenge of describing the sensation of taste: There simply isn’t a vocabulary that belongs to it. Wine drinking is a social experience, however, and enthusiasts yearn to share it with others so have borrowed from the visual realm to describe the incorporeal attributes of taste. Often shapes are used to describe the sensation of tannin: rounded, edgy, linear or pointy are things you might hear.

Tannins can be found all over. In fact, tannins are an integral part of all fruit flavor. The seed of every fruit has tannin. You might notice it when you suck on a cherry or peach pit. Grapes however have unique tannins that offer a distinct experience from tannins found in other fruits. Almost all cream of tartar found on the market today is made using tannins extracted from grapes. Though you don’t analyze the sensation of biting into an apple as critically as you might sipping wine, you would certainly notice and miss the tannin if it was gone.

Fruit isn’t the only place that we find tannin however. A vital reason that oak shares such an affinity with grape juice is that its own native tannins serve to compliment or contrast with the tannin found in grapes. All wood has tannin in it. Cherry and redwood both have very soft tannins and though they are nowhere near as heavily used in winemaking as oak is, they lend their tannins to wine with favorable results. Even within the oak family, the different species of oak tree (French, American and Slavonian) have distinctive tannin structures of their own. Oak tannins tend to be more “edgy” or “rectilinear”, and it’s this contrast to the more rounded tannins found in grape skins that can create complexity. The cooperage (barrel maker) can redefine the nature of the oak tannin by the manufacturing process. By toasting the barrel at cooler temperatures and by air drying it for longer periods of time, the cooper can round the corners of the tannins producing an oak that is more complimentary instead.

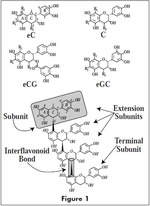

Clearly there’s a great deal of diversity of tannins out there. Every cluster of grapes contains several different types of tannin. The tannin in the stems, skins and seeds are all very different and while it’s generally agreed upon that the tannins found in the stem are too harsh and not ideal to include in the fermentation, there is debate about the quality and character of tannins found in the seed and skin. The prevailing opinion has been that seed tannins are harsher than skin tannins and therefore ought to be removed. Robert Rex disagrees with this notion and instead believes the reverse is true, which is a view shared by Dr. Roger Boulton, professor at UC Davis. Robert’s reasoning is that we use a fairly uncommon process known as whole berry fermentation where the grapes are never crushed and instead the juice ferments inside the berry. The difference is that the skins are never ripped apart, releasing the harsh tannins found inside. Our wines have notably soft tannins even though they are fermented along with all their seeds. Robert concluded that the least common denominator must therefore be the skins. Seed tannins tend to add structure to the center of the palate while skin tannins slide toward the back.

Tannin can be described as a sort of drying effect and if you ever have had a sip of wine and felt as if it coated the roof of your mouth, it was because there was too much tannin. To remove tannin, winemakers often make use of fining agents. In California, gelatin is commonly used and in France egg whites are the norm. At Deerfield, because of our gentle production techniques, we very rarely need to make use of fining agents and for that reason we are able to make wine that is vegan friendly.

Even white wines have a small amount of tannin in them. Almost all of the tannins are found in the skin and seeds which are immediately removed by pressing before white wine is fermented. Although our high-tech presses the grapes extraordinarily gently, some of the tannin from the skin is squeezed out. Furthermore, alcohol is the most effective agent at extracting tannins from the other parts of the grape and because the skins and seeds are removed before the alcohol is present (since the juice has not yet fermented), there are fewer tannins found in white wine.

The truth is that even the experts are dealing with an imperfect picture of exactly how tannin interacts with our taste buds. In this article Dr. James Kennedy presents a number of different theories as to the exact cause of the perception of tannin in wine. What we do know is that tannins gain complexity over time. As the years go by, all sorts of different flavor and color compounds floating in suspension in the wine combine with the tannin giving rise to endless new iterations. That’s why wine changes so dramatically with the passage of time and can sometimes go through periods of awkwardness or exceptionality.

tannin,

tannin,  winemaking

winemaking