harvest,

harvest,  vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture  Thursday, March 11, 2010 at 9:45PM

Thursday, March 11, 2010 at 9:45PM This week I'm going to take a break from the recap of the 2009 harvest to talk a little bit about what is happening at the winery right now. I promise though I'll be back to reminiscing next week.

Winter and spring have a very different feeling at the winery then does the late summer and fall. There's none of the clamor and fervor and anxiety of the harvest and instead it is replaced with a muted calm as the vines sleep for winter. The dormant vines need little attention as they save their energy for budbreak as the spring approaches. The wines in the cave are also sleeping, as it is often referred to, as they age and the molecules that form the taste and shape of the wine evolve into increasingly complex combinations. So the work the slows down and a winery that was understaffed with 12 crew members becomes comfortable with just two. Inside the cave there is little work to be done. The barrels must continue to be topped and a watchful eye is kept on them. Racking takes place more often than during the harvest. The pace of the lab tech's work continues as usual as a constant vigil of the developing wines must be kept. The winemaker can take this time to focus now on past vintages and creating the blends that will constitute future releases. This is an opportunity to bottle because of the lull in other commotion. The only problem is that it takes a large crew to bottle and the seasonal harvest crew has been disbanded. Aside from the occasional bottling though the crush pad is peaceful which I like because the surroundings feel more pronounced. There is this incredible shift in the hillside vineyards that line the valley from fall to winter as the rain revives the sun-dried grasses and turns the hills an emerald green and the vines conversely shift from green to brown as they shed their leaves and the shoots become wooden. In the vineyard workers prune the vines, removing all of the one-year-old wood from the arms of the vine so that when the buds start to blossom next spring the energy the vine expends will be channeled into fewer bunches of grapes. Here and there you can see a white pillar of smoke in a vineyard as the resulting piles of twigs are set ablaze. The air is crisp and chilled but the sun is warming and pleasant. The last rains will be over soon. It's a patient time of the year and in the coming weeks the juices of the plant will again begin to flow. The buds will break and the transformation of the plant will begin again as the cycle is renewed. Although it seems a long way off, I'm sure harvest will be upon us again before we know it.

harvest,

harvest,  vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture  Tuesday, April 27, 2010 at 2:46PM

Tuesday, April 27, 2010 at 2:46PM With the rain comes the flowers and with the flowers come the allergies, but in the Valley Of The Moon at least the budding vines are a condolence for the sniffles and bleary eyes. The rows upon rows of woody vines, protruding from the earth like an army of twigs, are renewing themselves and along the top of each trellis is the very beginning of a new wine's journey. When I came to the winery for harvest last August the vines were in full swing. Maybe not all of the grapes had yet undergone véraison (the coloring of the berry) but the 2009 crop was already quite mature upon my arrival.

So it was very exciting to find one day that suddenly a tiny layer of green had appeared atop each vine. It is also a remarkable example of how true the "micro-climate" theory really is: Growers and winemakers alike often say that a particular part of a vineyard produces superior grapes to another part only meters away and for that reason divide up a vineyard planted with the same varietal into seperate "blocks" that they feel have a slightly different terroir. While it may be hard to believe, I have to admit that the recent budding of our vineyards in ample evidence to support the idea. I was feeling a little left out because everywhere around us (and I mean up and down the entire valley) the vines were budding out while our vineyard appeared as if it had decided to hibernate for another year entirely. Right across the street our neighbors had vines with almost full leaves on them! Finally our vines came around and now every vine has happily sprouted. Also certain parts of each of our vineyards budded simultaneously while other blocks seemed to lag. Certainly there must be a great diversity of factors why vines that are so close to each other would be on different calendars but considering that they share equal amounts of sunlight it created an interesting puzzle. This set Ryan and I speculating on a range of possibilities such as a difference in elevation or sometimes more outlandish propositions. I suggested that as the sun set the shadow of the peak of the mountain covered one part of the vineyard sooner than the other. I eventually asked Robert what he thought and he attributed the difference not to heat of the surface but of the heat below ground: Our vines are lower than many of our neighbors and as we are situated right next to a wetland there is more water in the soil which keeps the roots cooler.

It has been a great pleasure waking up every day and inspecting the vineyard to see what progress the vines are making. They grow at an incredible pace! I knew that vitis vinifera was a vigorous plant but sometimes I feel like I can actually see it growing. I am beginning to now see the allure of the growing. Incredibly inflorescence (flowering of the vine) seems right around corner although it's not supposed to occur until sometime in May. I'm taking a series of photos of one of the vines so you'll be able to see its growth over the year. The temptation to name it is mounting... I'm thinking Vinnie but I'm open to suggestions! Until next time - Salut!

vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture  Wednesday, June 2, 2010 at 1:37PM

Wednesday, June 2, 2010 at 1:37PM Sonoma Valley’s hillsides are covered in rows of lush green leaves. At Deerfield the Organic Syrah vines are in full swing, blooming into great bushy hedges soaking up the sun and clamoring for attention. It’s remarkable how fast they’re growing. It seems like inches a day and I could swear that if you watch them closely you can see them grow. During this period of incredible vigor two things are happening right now in the vineyard: As I discussed in this week’s episode of Cellar Rat TV, our vines are going through inflorescence (or flowering). I had mentioned at the end of April that it looked like they were going to flower soon – but it turned out that they are right on time and the flowers are just beginning to form. That seems fortunate because this unusually wet May threatens the formation of grapes by unleashing a downpour on the fragile flowers, potentially destroying them or washing away the pollen. If that happens the result could be grape bunches with too few grapes on them or none at all. Luckily most of the flowers are still encased in the calyptra, the shell of fused petals, which hopefully will shield them from the rain. The weather is beginning to warm now and although some showers are promised later this week, I think the worst is behind us. Soon the flowers will have pollenated themselves and the vines will enter a short period called fruit set where the flowers transform into little immature grapes.

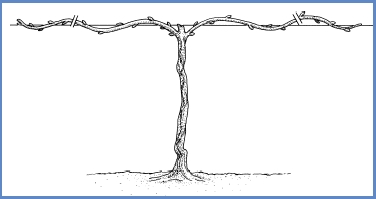

As the vines work to produce their fruit, the tendrils that support the leaves and clusters of grapes are beginning to snake outwards and are now long enough to tie to the trelise. If you thought pruning the vast vineyards in the winter was a challenge it seems easy compared to the tedious process of coaxing each vine into the desired shape. It requires a gentle touch because, unlike the wooded part of the vine, the green new growth is fragile and must be handled with care. At the same time some of the canopy might be reduced if the leaves seem too thick to allow the wind to flow through and keep the vines dry. I’ll talk more about the benefits of trellising at a later time but sufficed to say there is a multitude of reasons for having some sort of system which can look radically different because the shape of the vine itself is so malleable. The one we employ is the traditional double cordon method, which is by far the most commonly used system in California. The vine is split into two main arms called cordons which run in opposite directions horizontally along the bottom of the trellis. The new growth is trained straight upwards allowing the leaves to form a sheet that is evenly exposed to sunlight. The grapes hang down along bottom of each cordon allowing them to receive sunlight, air flow, and increase the ease of harvest. Just a small portion of the vineyard is done so far but slowly the growers are affectionately creating order out of chaos. The grape growers of Sonoma Valley still take a close, hands-on appoach, paying special attention to each vine which reflects their mindfulness of the principles of organic, sustainable, and biodynamic farming.

vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture  Wednesday, June 9, 2010 at 5:27PM

Wednesday, June 9, 2010 at 5:27PM When people stop by the tasting room they often ask me if the acres of sculpted vineyards are difficult to manage. The truth is that trellising the vines is a lengthy but crucial process. The use of a trellising method is arguably the most important tool in the grower's arsenal. The key to producing potent, flavorful berries is channeling the vine's energy into producing the fruit. Vitis vinefera is a vigorous plant and each year, if left to its own devices, will erupt into a jumbled leafy mass. But wine isn't made out of leaves. It's made out of delicious grapes. So there has to be a way to make sure that the precious energy the vine expends isn't wasted on growing more leaves than is necessary to adequately perform the photosynthesis required to nourish the plant. That's where trellising comes in. Among other things, the trellis allows the grower to restrict vegetative growth and also the fruit yield of each vine. As I mentioned last week, the trellising system also benefits the vine by creating a canopy that is evenly exposed to sunlight and is less dense. This promotes air circulation which is good for the respiration of the leaves and is also the first line of defense against mold and mildew. Over the years, humans have devised many clever and diverse ways to manipulate the shape of the vine. Although the cordon system is the most widely used in California, there are many different approaches used locally. All of these pictures were taken within a quarter mile of the Deerfield Ranch Winery.

Types of trellis systems:

The Guyot system, named for the French scientist who invented it, has become extremely popular since it was created in the 19th century. The vine is split into two arms called cordons which run horizontally in opposite directions along a wire with the shoots trained upwards.

The Vertical Shoot Positioned trellis (or VSP) is very similar to the Guyot design except that there are four arms along two different guide wires instead of two arms.

The cordon training system which also bears close resemblance to the Guyot system is the preferred method in America. All of Deerfield's organic syrah vines are trained in this fashion. One of the great benefits of this system is that it makes pruning relatively simple so that vineyard workers can perform the task perfectly with little training.

A relatively new addition to viticulture is the Scott Henry trellis, conceived of by a winemaker from Oregon. It is a variation of the VSP system where the shoots of the lower cordons are trained downward, creating two separate canopies.

The Gobblet is the oldest technique and is in declining use but it is still a core method in use throughout the Old World (especially Spain and Greece). Because there is no support system the vine takes on a bushy shape. The trunk, called the head, is pruned close to the ground and several main arms support the fruit. There are several disadvantages to this system however. It is extremely difficult to harvest the low-lying grapes. Several years ago I helped harvest a vineyard in Greece that made use of this system and my back ached for weeks after toiling hunched over all day. It also doesn't allow very good airflow and is very difficult to prune correctly.

There are many more types of trellising systems, some more exotic and creative than others. But as with most things, simplicity is often an essential element of good design. Next time you're at Deerfield take a moment to try and figure out which kind of trellis has been employed!

trellising,

trellising,  vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture  Wednesday, June 23, 2010 at 7:02PM

Wednesday, June 23, 2010 at 7:02PM As I was walking through the vineyards, fixing the irrigation and trellising the new growth, I noticed the rich, black earth that the vines were growing in. Soil composition dramatically impacts the finished wine and is a key reason that only certain regions are suited to growing wine grapes, which have very different needs than many crops. Most farmers would be envious of a land owner whose soil is nutrient-rich and fertile. Yet farmers that cultivate the land for the production of wine grapes know that quality wines are produced by the vine's struggle to create the seeds it needs to reproduce. If the vines are too well accommodated they will instead produce grapes that are large and have less flavor, appropriate for the table but not for the bottle. It is crucial for the soil to retain water adequately but also be extremely well drained. It is helpful if the topsoil can retain and reflect heat, aiding the ripening process. Most grapevines do well with a pH between 5 to 6 but some varietals do well in more balanced soils from about 6 to 8. Calcium, iron and magnesium are minerals that are essential to the life of the vine, as well as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium which are requisite to most plant life. However, grapevines are a remarkably tolerant and robust plant and can flourish in many different types of soils. Deerfield's vineyards, like much of Sonoma County, are composed of recent volcanic soil. The trace elements that the plant absorbs through its roots can dramatically impact the flavor of the grapes, although the idea that a wine contains the flavors of the minerals is somewhat of a myth. The famed wines produced from the slate soils of Germany's Mosel Valley are often described as possessing mineral flavors, but while soils can be accurately attributed to creating flavors ubiquitous to a specific terrior it is somewhat more difficult to pin down what exactly slate smells like. The field of soil science is one of the most extensively studied aspects of viticulture at oenological institutions around the world. But there is far more to a perfect bunch of Pinot Noir grapes than just the soil that the vines roots live in. Next time I'll describe the elements that make up terroir.

vines,

vines,  viticulture

viticulture