What Happened To Summer?

Thursday, August 5, 2010 at 2:44PM

Thursday, August 5, 2010 at 2:44PM A couple of days ago the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle informed us Californians that our cool summer was here to stay. Like everyone else I was looking forward to the heat after a particularly wet spring. That sun never really came and now that it's August I suppose that I'll just have to wait until next year for a proper summer. All of the crops seem to be waiting for the sun too. Everyone I talk to has the same story to tell: Their backyard gardens are about a month behind. The grapes are no exception. Growers around the Valley complain that their grapes are lagging about 3 weeks behind. Unripe clusters of grapes on August 1st

Unripe clusters of grapes on August 1st

At this rate, everybody jokes, they won't be ready to harvest until the December 1st. Typically, harvest starts at the end of August or the beginning of September. The concern is that they don't fully ripen before the heavy rains arrive. I've written about what can happen if that is the case in a past post. The harvest of 2009 was a similar story with late ripening grapes. It's during the challenging years that the talented winemakers stand out though, and last year Deerfield produced some spectacular wines. It is very strange that while girls are walking down the streets of Moscow in bikinis and the East Coast is seeing record highs that I find myself wishing I had brought my sweatshirt along. I have never put much faith in long term forecasts and I'm still holding out for the sun. It's only the beginning of August after all - there's plenty of time for beach weather. The seasonal pond in Kenwood Marsh is emptying on schedule so perhaps the grapes will ripen on schedule after all. The truth is that until the fruit is on the sorting table no one really knows what 2010 will be like for Northern California.

The European Grapevine Moth

Wednesday, August 11, 2010 at 4:11PM

Wednesday, August 11, 2010 at 4:11PM Ever since phylloxera decimated the vineyards of Europe in the late 19th century and wiped dozens of varietals off the face of the Earth, growers and winemakers around the world have paid keen attention to new pests that might revive the specter of another grape holocaust. Phylloxera was brought from North America to Europe. This time the Europeans have returned the favor. The European grapevine moth has been found in several vineyards in the Napa Valley setting into motion a whirlwind of activity. Lobesia botrana has completely adapted its lifecycle to that of the grapevine. The adults first lay their eggs on the vines in summer. The caterpillars then eats the fruit and crawls underneath the bark of the vine to form their cocoon in which they reside through the next winter. The moth, originally from southern Italy, has now been found throughout Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Russia. The battle against this pest has been waged for more than a century.

Lobesia botrana

Lobesia botrana

When the first vines in Europe started to inexplicably deteriorate, it was a long time before the nearly-microscopic phylloxera was discovered to be the culprit. It took even longer to determine how to combat the dreaded insect. Today, we benefit from a better understanding of ecology, sophisticated equipment and techniques, and agencies dedicated to protecting vital industries. The U.S. Department of Food and Agriculture has quarantined most of Napa County as well as parts of Sonoma and Solano counties and is trying to ascertain how it came to be here and what methods are needed to stop the spread. Strategies to combat the moth are already being implemented. One such attempt tries to mimic the female pheromone, luring unsuspecting males into a fruitless search for a mate and thereby interrupting the reproductive process. Another technique, with a nod to biodynamic principles, suggests promoting the populations of insectivorous bats and wasps that lay their eggs inside the moths. In California, traps have been set up throughout every grape growing region in the state to better understand the scope of the problem. Winemakers and growers are attending a series of seminars to become educated about the pest that are being hosted by the County Agriculture Commission.

European Grapevine Moth,

European Grapevine Moth,  pests

pests A Little More About Barrels

Wednesday, August 18, 2010 at 2:20PM

Wednesday, August 18, 2010 at 2:20PM Several weeks ago I talked about the profound relationship that wine shares with oak and the importance of the barrel maker to the winemaking process. The artistry of bending the wood of the oak tree to benefit the crafting of wine extends well beyond the domain of the cooper. The winemaker chooses very carefully which vessels his wine will mature in. The choice is far more complex than simply whether to use French or American oak. At Deerfield, one of the key elements we use to create such nuanced wine is the implementation of what are known as barrel schedules, or programs. A great deal of thought and planning is done by the winemaker to create a schedule to add depth to the wine. Each wine rests in a variety of different barrels, so for example a lot of Cabernet Sauvignon, maybe even just one exemplary block in a vineyard, is given a custom-tailored barrel program. What's more, when that Cabernet is included in a blend years later, a new barrel schedule is created for that blend. What is incredible to me is the understanding the winemaker has of the impact on the character of the wine that a specific barrel has. There are three factors to consider in choosing a barrel for the program. The type of oak the barrel is made of: French, American, Hungarian oak, have very different flavors. Usually, at Deerfield, a wine receives a mixture of French and American oak barrels. The overriding idea is that when the barrels are later blended together, the attributes of both will be present in the wine. The second factor is the tonnellerie, or cooperage, that produced the barrel. There is a great deal of room for expression during the creation of a barrel - the heat and duration for which the barrel is "toasted" greatly impacts the flavor of the wood. The same barrel can even be constructed out of staves of different types of oak. Or all the staves can be one type of oak and the heads another. There's lots of variation and innovation within the cooperage industry, and though barrel making is a craft steeped in tradition, ongoing experimentation has invigorated competition among the coopers. During harvest, representatives drop by with a case of beer for the crew hoping to get the ear of the winemaker and tout the strengths of their barrels. Indeed, there are many to choose from. Demptos, Radoux, Bel Air, Tonnellerie du Val de Loire, Saint martin, Kovacs Tokai, Seguin Moreau, Quintessence, Magrenan, Kelvin Cooperage, Sylvain, World Cooperage, Emeritage, Boutes Tonnellerie de France, Trust, Tonnellerie Remond are just a few brands that reside in Deerfield's cave. Each chosen for its unique qualities and carefully monitored for performance. And then many cooperages tout different lines of barrels like models of cars - luxury, durability, longevity, leather seats. The point is you've got options. Lastly, the age of the barrel (in terms of its use) is a significant factor. When a barrel is brand new it has an intense oak flavor and any wine aged in it will assume that intensity. After about four years of wine sitting in it, a barrel has pretty much used up all of the oak flavor. Barrels that are old and no longer have noticeable oak flavor are referred to as neutral barrels. They are still useful - they impart tannins and remove harsher ones and allow the wine to breathe. So usually a wine is aged in a combination of new, 1 year, 2 year, 3 year, and neutral barrels so that when the barrels are blended back together for bottling (or further blending) the resulting wine is well balanced. Also this gives the winemaker options for different blends. Perhaps a Tuscan style Sangiovese blend would benefit from a Cab Sauv that has been aging in new barrels. Here is part of the barrel schedule for 2009. On the head of most barrels you can see the type of oak, the year the barrel was made, the cooperage and the amount of toast. If you stop by the cave take note of what barrels are being used for each wine.

barrels,

barrels,  oak,

oak,  winemaking

winemaking The Anatomy Of A Bottle

Wednesday, August 25, 2010 at 2:17PM

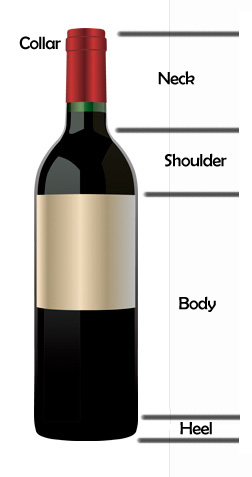

Wednesday, August 25, 2010 at 2:17PM Bottling last week got me thinking more about the  beautiful glass vessels whose shape we associate so strongly with wine. The anatomy of the bottle borrows much of its terminology from the anatomy of the human body: The bottom of the bottle is called the base, heel or insweep. The characteristic indentation on the bottom of the wine bottle is known as the kick-up, push-up or (perhaps most commonly) the punt. The punt if you’re wondering, as I often have, is primarily to add strength to the bottle but it also aids in collecting any sediment that may be present in the wine. This was a critical innovation and it’s likely that we would not have sparkling wine today without it. The body is the portion of the bottle where the sides are straight. The slope that leads from the body to the neck is appropriately called the shoulders and this is where bottles derive most of their style. The raised ring around the neck is called the collar which adds strength to the bottle and allows any sort of tamper-protective covering to grip the bottle. The mouth of the bottle you can probably surmise is the opening on top. The finish refers to the style of the neck as it relates to how the wine is sealed. For example a wine could have a cork finish or a screw-cap finish. All wine bottles have these features, they simply differ in appearance.

beautiful glass vessels whose shape we associate so strongly with wine. The anatomy of the bottle borrows much of its terminology from the anatomy of the human body: The bottom of the bottle is called the base, heel or insweep. The characteristic indentation on the bottom of the wine bottle is known as the kick-up, push-up or (perhaps most commonly) the punt. The punt if you’re wondering, as I often have, is primarily to add strength to the bottle but it also aids in collecting any sediment that may be present in the wine. This was a critical innovation and it’s likely that we would not have sparkling wine today without it. The body is the portion of the bottle where the sides are straight. The slope that leads from the body to the neck is appropriately called the shoulders and this is where bottles derive most of their style. The raised ring around the neck is called the collar which adds strength to the bottle and allows any sort of tamper-protective covering to grip the bottle. The mouth of the bottle you can probably surmise is the opening on top. The finish refers to the style of the neck as it relates to how the wine is sealed. For example a wine could have a cork finish or a screw-cap finish. All wine bottles have these features, they simply differ in appearance.

Burgundy

Burgundy Hock

Hock Claret

Claret

Like so much of the wine world, the modern bottle is a reflection of both function and tradition. Bottles have likely been used to store wine since the time of Christ but it wasn’t until the 17th century that glass bottles became common. The shape of the wine bottle has evolved over time but today there are several conventions that are firmly rooted in culture. The two most popular styles are the claret bottle, which originated in Bordeaux, and the burgundy bottle. The claret was popularized in the mid 19th century though it is possible it was in use by the French well before then. It has a body that features almost parallel sides although sometimes there is a slight taper where the shoulder is wider than the heel (this greatly complicates labeling). The body is long and narrow and the shoulder is short and sharply curved. The burgundy bottle is fatter with long shoulders that when combined with the neck is about equal to the length of the body. The punt is usually smaller except for champagne bottles which require the added strength. The bottles are associated closely with not only region but also varietal. Pinot Noir is always bottled in the burgundy style bottle, as is Chardonnay. Cabernet Sauvignon and other Bordeaux varietals such as Merlot are strongly associated with claret bottles. A third prevalent style that is slightly less common is the Hock or Rhine shape. These slender bottles have curves that flow from the heel to the collar so that the body shoulder and neck flow together. This style is typically associated with the German varietals Riesling and Gewurztraminer. There are many subtle nuances within each style and the options of bottles available to a winemaker are staggering. Deerfield always uses high quality glass because after all, the bottle that the wine is in represents it, like the clothes that you choose to wear.

bottles

bottles Harvest 2010 Begins!

Wednesday, September 1, 2010 at 3:04PM

Wednesday, September 1, 2010 at 3:04PM There is much to be done on the crush pad and in the cave before the first grapes show up. The new crew is almost completely assembled. There are some familiar faces and some new ones. Cecelia, the assistant winemaker, is in charge of hiring the crew and this year is definitely a cast of characters. Aaron and Cruz are the year-round cellar staff – they top the barrels, rack them and maintain the sleeping wines during the off-season. But harvest requires much more manpower so joining the team is a couple of veteran cellar rats including Dean, the San Diego surfer, and Ryan, our Texan talent, who has been working for us as Regional Sales Manager since the end of last harvest. Amanda, the lab technician, was due to depart to continue her studies but I suppose the allure of fermenting grapes was too much to resist because she came back to work the harvest. A new addition to the team is a fine young gentleman from Louisiana named Will, who, with his pleasing southern drawl, also brings a lifetime of farming experience. He knows the long hours that harvest requires, regardless of the crop. Even though there won’t be any fruit to crush for several weeks, the rat pack will have plenty of work to keep them busy. As I mentioned at the start of the 2009 harvest, the machinery required for the crush has been sitting idle for the better part of the year and must be sanitized and put in working order. In fact, the first order of business will be to clean the entire cave from top to bottom. Keeping the cave clean during harvest is a difficult task with the constant influx of sticky grapes so starting with a clean slate is crucial. It’s also an opportunity for the newbies to learn the ropes. I spent my first days topping barrels and racking wines which familiarized me with how to use most of the equipment and our sanitization protocols. Before we know it the first of the grapes will be rolling onto the crush pad from vineyards in hotter climates and Harvest 2010 will be underway. Our grapes greatly benefited from the heat last week and have been rapidly undergoing veraison, or the changing colors of the grapes from green to red. In a few of the rows exposed to the sun it’s almost at 90%. Though the grapes are ripening slowly this year, Robert tells me this can actually be a great benefit to the wines. Slow ripening leads to deep and complex flavors, but the trick will be to get them off of the vines before heavy fall rains.