fermentaton,

fermentaton,  winemaking

winemaking  Wednesday, January 19, 2011 at 12:03PM

Wednesday, January 19, 2011 at 12:03PM Every day during harvest, the lab tech goes to each fermenting batch of wine and tests the level of Brix (a measurement of the percentage of sugar). As the wine ferments the Brix steadily drops until it reaches zero, indicating that all of the sugar has been converted by the yeast to alcohol. But occasionally during the fermentation, the chart hanging from the tank where the tech records posts the readings shows the same result day after day. That’s when you know you’re dealing with a stuck fermentation. The yeast has died off, become less active or stopped multiplying. Without treatment, the result would be syrupy sweet juice. It can be scary, but with the right techniques, a skilled winemaker can save the day. Our gold-medal-winning Buchigniani/Garcia Dry Creek Valley Zinfandel gets stuck every year because it comes in at such high Brix.

High Brix means high sugar and sometimes that creates a situation in which the yeast has made so much alcohol that before its finished consuming all the available sugar, the alcohol is high enough to kill the yeast. There are other reasons that primary fermentation can get hung up though. Sometimes the problem is as simple as the tank is too cold for the yeast, and they slow down quit doing their job. Occasionally a harmful bacterium from the vineyard such as Acetobacter or a mold such as Botrytis is producing acetic acids, increasing the volatile acidity and thereby disturbing the yeast. Sometimes there are not enough nutrients in the juice to sustain the yeast. In all cases, as soon as the winemaker has discovered that their wine is stuck, they immediately press the wine off of the skins so that they can better control the process.

Additionally, secondary fermentation (or malolactic fermentation), in which bacteria converts harsh malic acids to softer lactic acids, can outstrip the pace of the yeast. This is often the case with stuck fermentations and the procedure is to let the beneficial bacteria Oeonococcus and Lactobacillus run their course, at which point the primary yeast fermentation can be restored. The wine is then racked off of its lees before restarting the regular fermentation. Rice hulls (which are like the husks of rice grains) are added to neutralize harmful toxins in the juice.

The process of restarting fermentation varies from winemaker to winemaker. At Deerfield we begin by taking some of the wine from the tank and making a mixture of 50% wine, 50% water, fresh yeast, yeast food, and other nutrients which we then allow to start fermenting. This mixture is then added to the tank which is kept at 70⁰F and carefully monitored. When the Brix drops by half of what it was when it became stuck another mixture is prepared. This time the ratio is 75% wine and 25% water. Again when the Brix halves a final mixture is readied. The last mixture includes just wine from the tank and the remaining nutrients the yeast needs. The idea is to slowly acclimate the yeast to the environment of the wine so that it is happy, healthy, and well prepared to do its job. Usually this will resolve the problem and the fermentation will finish.

Maybe we can all learn something from the yeast: When you get stuck, take a bath, give yourself a fresh start, then slowly ease back into it and you’ll solve the problem in no time!

fermentaton,

fermentaton,  winemaking

winemaking  Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:51AM

Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:51AM  Sometimes it seems like the world of wine has had a line drawn in the sand. On one side there are fruity and light white wines and on the other side there are the structured and more tannic reds. But occupying the no-mans-land between these two different worlds is Rosé. Neither a true white or a true red, this pink juice shares characteristics of both.

Sometimes it seems like the world of wine has had a line drawn in the sand. On one side there are fruity and light white wines and on the other side there are the structured and more tannic reds. But occupying the no-mans-land between these two different worlds is Rosé. Neither a true white or a true red, this pink juice shares characteristics of both.

All red wines draw their color from the skins of the grape and in this sense Rosés are no different. There are several different techniques that winemakers use to achieve the distinctive style of Rosé. Sutter Home's technique which it uses to produce their um...ubiquitous...*ahem* White Zinfandel is the product of a winery accident where red wine was accidentally added to a white wine tank and to this day, most of the Rosés on the market are produced by simply blending red and white wines. Alternatively, when the winemaker’s intent is to produce a Rosé from the beginning, grapes are harvested at very low Brix to achieve a light wine with low alcohol. Unlike red wines that are fermented along with their skins throughout the entire process of primary fermentation, Rosés are only briefly in contact with their skins before they are pressed, often only for as short a period as a few hours.

Deerfield uses a traditional approach to making Rosé. Deerfield produced a Rosé in 2009 and our latest one, the 2010 Checkerbloom Rosé, was just released this past week. Deerfield uses a traditional process known as Saignée (which means "bleeding off") to make our Rosé. In this process grapes that are picked at a high Brix, which have too much sugar that will likely produce a wine with too high alcohol yet beautiful ripe fruit flavors, are macerated and some of the juice is "bled off" to reduce the skin to must ratio. This extra juice is ideal for creating a Rosé. Rosé can be made out of many different varietals or a blend. The juice we use to produce our Rosé was bled off of our 95 point Old Vine Zinfandel which invariably is harvested at high Brix. Already colored by its contact with the skins, we treat the juice quite differently than either a normal red or white fermentation. We ferment at a low temperature to slow the process, and in neutral oak barrels which is typically a treatment we reserve for Chardonnay. The barrel fermentation develops softer tannins and lengthens the mouthfeel. Even though this wine is fermented without its skins like a white wine, we use a strain of red wine yeast that is known to accentuate the fruit character. This is what makes our Rosé stand out - it has bold fruit flavors and body, yet it is light and approachable.

rose,

rose,  winemaking

winemaking  Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM

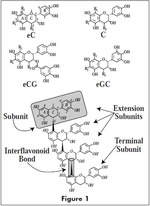

Friday, March 25, 2011 at 3:49PM  Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

Molecular Structure Of TanninThere are a few essential elements in the composition of wine that define it. Among those elements is tannin. Without tannins, wine just wouldn’t be wine. Understanding a little bit about what tannins are allows you to better understand the marvelous sensation you experience when you have a sip of wine. A unique and complex combination of compounds, tannin isn’t so much a particular taste as it is sensation. A good way to think about it is that along with the acids, tannins are the structure of the wine and the particular flavor nuances sit on top of that structure. It’s the shape of the wine.

It’s a tricky concept to translate to words. We’re visual creatures and humans have developed a huge vocabulary to communicate to one another things we see. But there wasn’t a word for red, how would you describe it to someone else? …or to someone who’s never seen it? That’s the challenge of describing the sensation of taste: There simply isn’t a vocabulary that belongs to it. Wine drinking is a social experience, however, and enthusiasts yearn to share it with others so have borrowed from the visual realm to describe the incorporeal attributes of taste. Often shapes are used to describe the sensation of tannin: rounded, edgy, linear or pointy are things you might hear.

Tannins can be found all over. In fact, tannins are an integral part of all fruit flavor. The seed of every fruit has tannin. You might notice it when you suck on a cherry or peach pit. Grapes however have unique tannins that offer a distinct experience from tannins found in other fruits. Almost all cream of tartar found on the market today is made using tannins extracted from grapes. Though you don’t analyze the sensation of biting into an apple as critically as you might sipping wine, you would certainly notice and miss the tannin if it was gone.

Fruit isn’t the only place that we find tannin however. A vital reason that oak shares such an affinity with grape juice is that its own native tannins serve to compliment or contrast with the tannin found in grapes. All wood has tannin in it. Cherry and redwood both have very soft tannins and though they are nowhere near as heavily used in winemaking as oak is, they lend their tannins to wine with favorable results. Even within the oak family, the different species of oak tree (French, American and Slavonian) have distinctive tannin structures of their own. Oak tannins tend to be more “edgy” or “rectilinear”, and it’s this contrast to the more rounded tannins found in grape skins that can create complexity. The cooperage (barrel maker) can redefine the nature of the oak tannin by the manufacturing process. By toasting the barrel at cooler temperatures and by air drying it for longer periods of time, the cooper can round the corners of the tannins producing an oak that is more complimentary instead.

Clearly there’s a great deal of diversity of tannins out there. Every cluster of grapes contains several different types of tannin. The tannin in the stems, skins and seeds are all very different and while it’s generally agreed upon that the tannins found in the stem are too harsh and not ideal to include in the fermentation, there is debate about the quality and character of tannins found in the seed and skin. The prevailing opinion has been that seed tannins are harsher than skin tannins and therefore ought to be removed. Robert Rex disagrees with this notion and instead believes the reverse is true, which is a view shared by Dr. Roger Boulton, professor at UC Davis. Robert’s reasoning is that we use a fairly uncommon process known as whole berry fermentation where the grapes are never crushed and instead the juice ferments inside the berry. The difference is that the skins are never ripped apart, releasing the harsh tannins found inside. Our wines have notably soft tannins even though they are fermented along with all their seeds. Robert concluded that the least common denominator must therefore be the skins. Seed tannins tend to add structure to the center of the palate while skin tannins slide toward the back.

Tannin can be described as a sort of drying effect and if you ever have had a sip of wine and felt as if it coated the roof of your mouth, it was because there was too much tannin. To remove tannin, winemakers often make use of fining agents. In California, gelatin is commonly used and in France egg whites are the norm. At Deerfield, because of our gentle production techniques, we very rarely need to make use of fining agents and for that reason we are able to make wine that is vegan friendly.

Even white wines have a small amount of tannin in them. Almost all of the tannins are found in the skin and seeds which are immediately removed by pressing before white wine is fermented. Although our high-tech presses the grapes extraordinarily gently, some of the tannin from the skin is squeezed out. Furthermore, alcohol is the most effective agent at extracting tannins from the other parts of the grape and because the skins and seeds are removed before the alcohol is present (since the juice has not yet fermented), there are fewer tannins found in white wine.

The truth is that even the experts are dealing with an imperfect picture of exactly how tannin interacts with our taste buds. In this article Dr. James Kennedy presents a number of different theories as to the exact cause of the perception of tannin in wine. What we do know is that tannins gain complexity over time. As the years go by, all sorts of different flavor and color compounds floating in suspension in the wine combine with the tannin giving rise to endless new iterations. That’s why wine changes so dramatically with the passage of time and can sometimes go through periods of awkwardness or exceptionality.

tannin,

tannin,  winemaking

winemaking  Thursday, May 26, 2011 at 4:46PM

Thursday, May 26, 2011 at 4:46PM I’ve often talked about how winemaking is the meeting ground between art and science, how chemistry aids us in our understanding of the craft but at the end of the day it’s all about taste. Yesterday I had the pleasure of joining Winemaker Robert Rex and the Custom Crush Winemaker Cecilia Valdivia as they sat down to begin formulating the blend for the 2007 vintage of Deerfield’s immensely popular Red Rex. For those of you not familiar with this particular wine, I’ll summarize by saying it is a mega-blend, the likes of which would only be produced in California because it breaks all the rules. In this blog I wrote about how unlike Coca Cola, two vintages are never the same. For this reason Robert never follows a set formula, he simply seeks to make the best possible wine from the grapes Mother Nature deigned to give us. And so the character of the wine can change dramatically though the goal remains the same: To produce a complex, approachable, full-bodied wine that covers every inch of your palate. This year’s Red Rex is a fascinating blend produced from 7 varietals, 17 vineyards, and no less than 25 different lots (individual batches of wine). While this may seem like an “everything-but-the-kitchen-sink” blend, in fact the exact opposite is true: Each component was carefully considered and selected because it will add a specific desirable feature to the finished wine.

So where does a winemaker start? Well of course, it starts in the vineyard. All of the grapes from the different vineyard produced separately as their own wines. As these wines are made, the winemaker becomes intimately familiar with each of them. So on paper, Robert first begins to plan out which wines he thinks ought to be included in the blend and in what amounts. A Cellar Rat has a busy day carefully pulling samples from all 25 different lots. Then a representative blend of all the wines is made. Next comes the fun part – we tasted through every single lot of wine so Robert could reassess each component of the blend individually. The only way to improve your palate is by practice and yesterday I felt as though my palate had a crash course that would normally have taken months or years. Tasting each wine and comparing and contrasting them with the others really allows you to see how each one is different and learn what your likes and dislikes are. Also certain factors alter your perception so having a winemaker there to explain what you’re experiencing is invaluable. For example, higher acidity can create the impression of high alcohol when in fact that is not the case. Having the lab results of the actual amounts of acids, alcohol, pH balance and residual sugar is helpful too because it allows you to understand the correlation between the various components.

After every instrument was individually experienced, we next listened to the whole concerto. It was incredible how it was possible to detect and pick out the individual characteristics of the different wines we had tasted earlier even though they were present in such miniscule amounts. Now that the winemaker has a better idea of the wines and how they harmonize, Robert will tweak the ratios of the blend and come back for round two with his adjustments. This time instead of tasting every component we will taste several different versions of the blend to fine tune the orchestra and find the one that works best. I expect that the 2007 Red Rex will receive a standing ovation when the house lights come up.

blending,

blending,  tasting,

tasting,  winemaking

winemaking  Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 11:03AM

Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 11:03AM Deerfield Ranch Winery focuses on what we call “clean” wine. Clean wine is low in both sulfites and the histamines that are created by the yeast. What this means to you is that you can enjoy Deerfield wines without the fear of the dreaded red wine headache or a sulfite hangover the next day. You can read more about it here, but the gist is that the yeast produces histamines to protect themselves when they encounter toxins in the fermentation process. We make sure the yeast only find what their looking for when doing their job in the fermentation tank by feeding them a healthy diet, sorting our grape three times to ensure only beautiful fruit is present, and by maintaining rigorous sanitation procedures.

We have our own water treatment facility we recycle 98% of all water that we use. You take a tour of the facility with the winemaker on Cellar Rat TV. In conjunction with our own well, we’ve created a model for what a sustainable winery can be. We recently added a state-of-the-art ultra violet light sanitation system that completely sterilizes all of the water at Deerfield without the need to use any chemicals. The system passes the water through three ultra violet light chambers that irradiate the water in a continuous flow with ultra-violet light (trust me, NOT a bad thing) so that no microbes come out the other end. We’re thrilled to add this to the winery because it guarantees us that the water we use in the winemaking process is completely pure.

Making clean wine isn’t just about one thing though. It requires a concentrated and thoughtful effort at every stage of the winemaking process, from the vineyard to the bottling truck. It’s worth the effort though. I personally am terribly affected by sulfites in wine. We use sensitive equipment to gauge exactly how much oxygen is dissolved in the wine and then add only enough SO2 to seek out and bond with the oxygen, leaving behind only inert SO3. Often when our wines are first release the SO2 is lower than 10 parts per million which is below the human threshold. That number even decreases as the wines age. For those people (like the winemaker’s wife, PJ) who suffer from headaches that make drinking red wine an awful prospect, Deerfield offers a delicious revelation. If you are one of those people, go ahead, try a glass of Deerfield! You won’t be the first person to discover that you can enjoy red wine again.

clean wine,

clean wine,  water conservation,

water conservation,  winemaking

winemaking